The Big Picture: The Power of Denial in the Conservative Movement

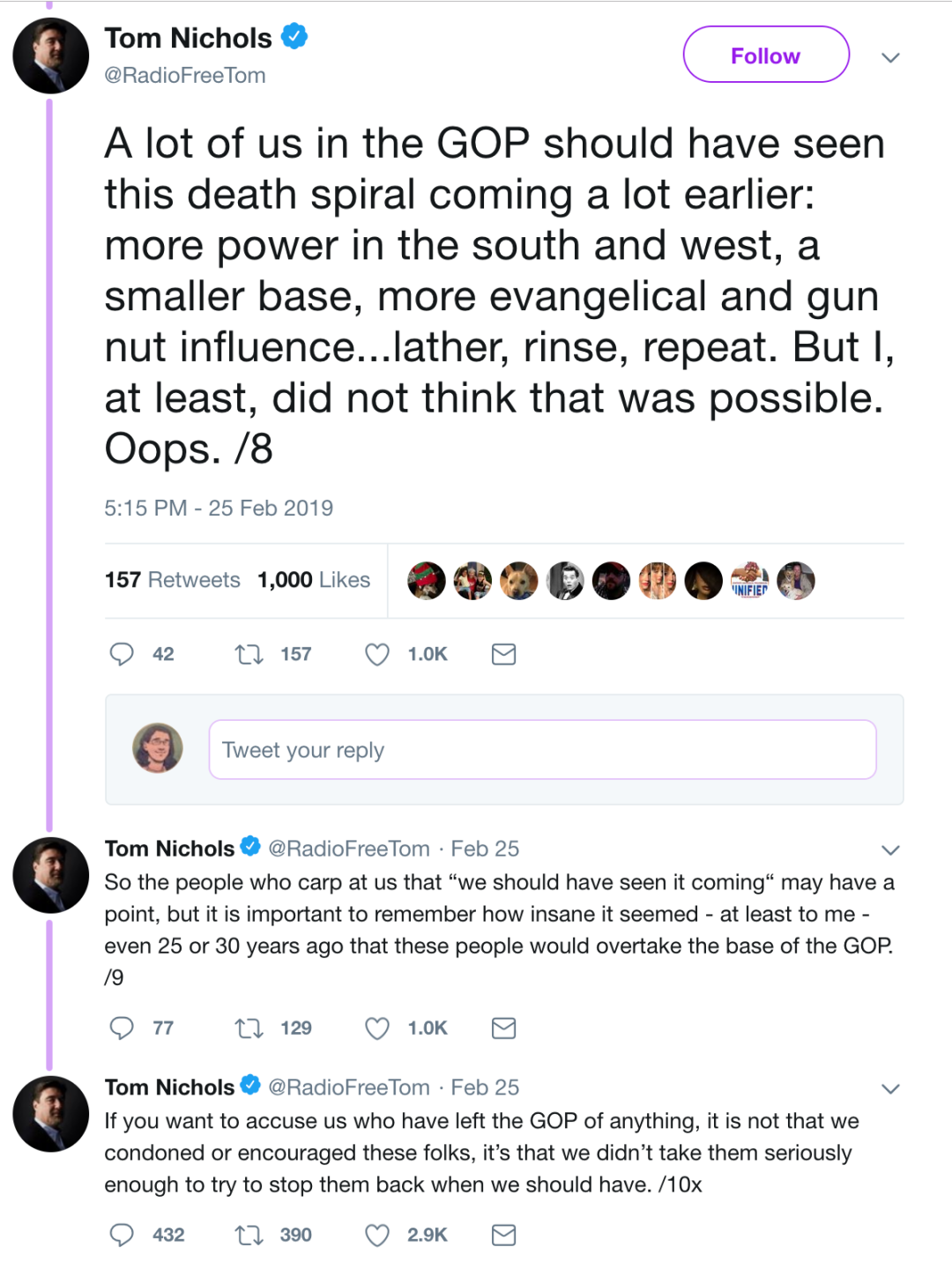

If there’s one consistent thing that many #NeverTrump conservatives have tried to get the American public to believe, it’s that the only problem in the conservative movement and the current iteration of the Republican Party is Donald J. Trump. If we could just get rid of Trump, they have implied on many occasions, everything would be fine. This is an incredibly naive, self-serving, and, almost certainly in many cases, intellectually dishonest, point of view. As it has become increasingly evident that it is precisely white evangelicals who are Trump’s base, however, the discussion has shifted somewhat. To give credit where credit is due, Tom Nichols has been more honest than most about white evangelicals’ role in radicalizing the GOP, although I think he is much too unconcerned about the state of American conservatism in general, and he seems not to recognize how failure to move left on issues like universal healthcare, student debt, and extreme inequality is going to keep social tensions high in the United States.

In any case, as it has become impossible for the media to ignore the fact that white evangelicals are far and away Trump’s most supportive demographic, and therefore his base, other conservative thought leaders have taken the less honest tack of normalizing evangelical extremism, essentially telling us to just sit tight, don’t be overly mean to evangelicals, everything will be fine. Enter Charlie Sykes’ and William Kristol’s new project, The Bulwark, which they created as a space for conservative commentators who object to Trumpism after Clarity Media closed down The Weekly Standard. The Bulwark bills itself as “a forum for rational, principled, fact-based, conservative commentary.”

It’s unfortunate, then, that evangelical political scientist A. J. Nolte’s article, “Why Did Evangelicals Flock to Trump? Existential Fear,” commits many sins of omission and flaws in logic, all of which just so happen to serve to paint right-wing evangelicals in a more sympathetic light than they deserve. If Kristol and Sykes don’t want to be seen as complicit in Trumpism, then they shouldn’t be printing articles that paint Trump’s base as essentially benign and capable of pluralism. But that’s precisely what they’ve done in this case, though, to be fair, in a manner no more egregious than what one frequently reads in the pages of The Atlantic, which just serves to illustrate how much work is left to do in order to get the American public sphere to treat evangelical authoritarianism with sufficient seriousness as a threat to democracy and human rights.

The Context: Why Can’t I Just Be Nice to “Respectable” Evangelicals?

I pitched a response to Nolte’s piece to two editors at different outlets, both of whom rejected my pitch with variations on “What’s The Bulwark? Who’s A.J. Nolte?” But given that Nolte’s piece gained some serious traction on Twitter, and that, with names like Sykes and Kristol behind it, The Bulwark is sure to gain recognition relatively quickly, I still think it’s worth writing a response. Beyond the issue of name recognition, in Twitter exchanges (both public and in DMs), where I’ve already raised my objections to Nolte’s anlaysis, I’ve been challenged by those who find my critical response to Nolte too harsh, because ostensibly any move by evangelical intellectuals to criticize their own is a “baby step” to be welcomed. To which I say: pardonne-moi, my friends, but #YouDontKnowEvangelicals.

“Respectable” evangelicals lobbing some mild criticism at their own, while engaging in a form of deflection we can refer to as the #NotAll defense, has been part of the evangelical ecosystem for a good long time. Far from reining in radical evangelicals, evangelical scholars grubbing for “moderate” brownie points only serves to create plausible deniability about the rot at the very core of an authoritarian version of Christianity grounded in a theology of “biblical inerrancy” that serves to uphold white supremacist patriarchy.

Search far and wide for examples of conservative American Protestant leaders and institutions policing the rightward border of their movement in a serious way, and you’ll come up empty, unless you count some handwringing when, say, actual swastikas show up on conservative Christian college campuses. Meanwhile, evangelicals fiercely police the leftward boundary of their movement. To draw from my own investigative journalism on evangelical higher education, examples of censorship of student newspapers, litmus tests in hiring, and the purging of moderate to liberal faculty abound.

“Respectable” evangelicals like Nolte want to distract us from these realities, about which, in fairness, they may also be fooling themselves. But the evidence is copious, for those who have eyes to see, so to speak. And at the end of the day, evangelicals like Nolte present us with a self-serving, distorted view of white evangelicalism that works to normalize extremism and to prevent the U.S. public from addressing a serious problem–namely, that fundamentalism, of which conservative evangelicalism absolutely is a variety, is incompatible with pluralism, and that is why fundamentalists in power will work to dismantle democracy.

For a good example of how this is happening right now, look no further than the influence of evangelicals at the very center of the Trump regime: at the unprecedented access Trump gives his evangelical advisory council while excluding religious leaders of other faith traditions; at Ralph Drollinger of Capitol Ministries conducting weekly radical right-wing Bible studies with Vice President Mike Pence and Trump cabinet officials; at the fact that Trump is pursuing the radical evangelical agenda more vigorously than any previous Republican president, even George W. Bush, who was not about to do something so rash as to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem on behalf of rapture believers. Trump is also particularly vigorous in the appointing of far right-wing federal judges and in pursuing authoritarian initiatives such as the Muslim ban and the transgender military ban, both of which are popular with evangelicals, many of whose lobbying institutions, such as Tony Perkins’ Family Research Council, are designated anti-LGBTQ hate groups by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Nolte suggests that it is “existential fear” driving evangelicals to support Trump, and he’s not exactly wrong. However, his framing makes Trump the problem, when arguably white evangelicals are using Trump more than he is using them. It also ignores the fact that “existential fear” in the form of paranoia has always characterized the right-wing evangelical ethos, regardless of the level of actual external threat. This is part and parcel of authoritarianism, and it is absolutely natural that a right-wing authoritarian demographic would find justifications for supporting a right-wing authoritarian president, regardless of differences in style. By ignoring authoritarianism as a defining feature of conservative evangelicalism, Nolte normalizes extremism and leaves us with breezy bothsidesism and false optimism, when nothing short of the decoupling of right-wing radicalism (embodied more in the white evangelical population than any other demographic) from political power will set the U.S. on a course away from authoritarianism and toward functional democracy. In other words, Nolte’s approach to this problem is de facto just another example of the slick evangelical PR machine in action.

This is not the first time I have taken an evangelical intellectual to task over a mildly critical but also misleading and ultimately self-serving piece that many others, including liberals and progressives and many people who should have known better, praised to the skies. Last year, I broke down what was wrong with a wildly popular and much discussed essay published (where else?) in The Atlantic by Wheaton College and George W. Bush administration alum Michael Gerson, whose current position as a Washington Post columnist gives him greater name recognition than Nolte. In critiquing Nolte’s similar essay, I will try not to be too redundant.

In fairness, I should also note that Gerson very much surprised me when he actually called for Americans to vote for Democrats for the House in the 2018 midterm elections. I still don’t think he fully understands the depth of the rot in the Republican Party, however. It seems to me that in the short to medium term, Democratic dominance throughout the federal government, and in as many state governments as possible, is the only thing that will force the GOP to reform or die so that it can be replaced by a more reasonable conservative party. In the meantime, the support of “respectable” evangelicals like Gerson for tax cuts for the rich, and their lecturing of Democrats about a supposed need to move to the right–as if the whole country’s radical shift to the right over the last few decades, a shift that Gerson helped build while working with Karl Rove, is not at the root of our current crisis–indicate to me that our “reasonable” conservatives are still extremely out of touch.

For as much as they love to talk about how “reasonable” they are, they have not become nearly reasonable enough to face their own failures, and to understand that the country must shift hard left in order to come back to a functional center. If they fail to come around on this point, then all their attempts to distance themselves from Trump–the logical result of the conservative movement they built and a symptom of what the U.S. Right has become–are but a resounding gong and a clanging cymbal.

Sins of Omission: Nolte on Evangelicals, Fear, and Imagined Millennial Moms

Keeping the background and context established above in mind, let’s now get to a closer look at Nolte and his commentary on evangelicals and Trump. Because this is my blog and I therefore have the space and the editorial authority, I am going to take a pretty detailed look at Nolte, as his affiliations and commitments do have bearing on how seriously we should take him when he claims, for example, to support pluralism. But let us start at the beginning. Already in the introduction to his essay, Nolte’s rhetoric causes me to arch an eyebrow:

Of all the developments that have come along with Donald Trump’s capture of the Republican Party, few have been as unexpected as his robust support among conservative white evangelicals. What caused these socially conservative voters to embrace a candidate who built his brand on values so strikingly dissimilar from theirs? Why have many evangelicals gone so far as to actually uphold Trump’s values as a virtue in our current political moment?

It’s not that there’s anything here that is, strictly speaking, false. I would of course like to interrogate this notion of Donald Trump “capturing” the Republican Party, rather than being the natural expression of a radicalized party that has become essentially authoritarian, but I would also press Nolte on the “unexpected” embrace of Trump by evangelicals and of their supposed values that conflict with Trump’s. To be sure, pundits have scratched their heads over these questions, and evangelicals distinguish themselves from Trump on the level of style and rhetoric (although over time he has learned to parrot their key talking points more effectively).

But as any exvangelical will tell you–and the pundits should have started listening to us much sooner–conservative, mostly white evangelicals have always primarily valued power and control. The ongoing revelation of their vast hypocrisy regarding sexual abuse and cover-ups is ample evidence that purity culture is just the flip side of rape culture, and Trump embodies only a brasher, ruder form of patriarchy than the one they embrace. That Trumpism is a resurgence of white supremacist patriarchy, however, and that there is a clear link between this and the solid support of Trump by white evangelicals, is undeniable. While many white evangelicals have learned to deny that they are racist, we have ample data to show that they are far and away America’s most nativist demographic. Their self-reported “positive feelings” toward racial minorities simply cannot be taken at face value when their voting patterns and preferred policies are immensely protective of white privilege and harmful to racial minorities.

Moving on, Nolte situates himself relative to his subject as follows: “I come to the question both as a political scientist and as a friendly observer of, and by some definitions, a participant in, the world of conservative white evangelicalism, who also did not vote for Trump and remains deeply Trump-skeptical.” This clearly disingenuous “by some definitions” hardly constitutes full disclosure for an assistant professor of government at a school that was literally founded by Pat Robertson himself, as Christian Broadcasting Network University. Robertson remains chancellor of the school, which was renamed Regent University in 1990 and is closely associated with radical Pentecostalism. While, much like Wheaton College, Regent has pretensions to academic respectability, it is still thoroughly a right-wing evangelical school, with its student handbook forbidding “homosexual conduct” and describing “heterosexual marriage as God’s intended context for complete sexual expression to occur.” The school even going so far as to define every employee as a “minister” in its Christian Community and Mission Statement.

In fact, the statement presents the responsibilities of Regent’s community members to uphold the university’s mission–“Regent University serves as a center of Christian thought and action to provide excellent education through a biblical perspective and global context equipping Christian leaders to change the world”–in a well-nigh totalizing framework:

Regent subscribes to the Christian belief that all of its activities, including the duties of every Regent representative, should express Regent’s beliefs and be rendered in service to God as a form of worship. Therefore, all Regent activities further Regent’s mission and are an exercise and an expression by Regent and by each Regent representative of Regent’s Christian beliefs.

This doesn’t exactly leave a lot of wiggle room for academic freedom, nor does the required statement of faith that Regent employees are required to sign. While the statement doesn’t explicitly demand adherence to the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, it does require belief in biblical infallibility, which in practice generally redounds to the same thing, in addition to requiring belief in the Trinity, the virgin birth, the particularly ugly understanding of Christ’s death and resurrection known as penal substitutionary atonement, belief in Christ’s return, and a commitment to “worldwide evangelism.”

Can a person who adheres to these very specific beliefs, metaphysical propositions that are not grounded in facts accessible to all, and that are attached to an imperative to convert others to said metaphysical propositions, produce serious, authentic scholarship? And can such a person genuinely commit to the pluralism that Nolte claims he supports? To the first question I must answer yes, with one important caveat: the closer the subject being studied is to such a person’s religious ideology, the more the intellectual output is sure to be ideologically skewed, and this is one reason why allowing evangelicals the exclusive ability to define their own narrative to the public is bad for civil society. On the second question, while such a commitment may not be impossible for some individuals, it is certainly in tension with the desire to see the entire world converted to fundamentalist Christian beliefs.

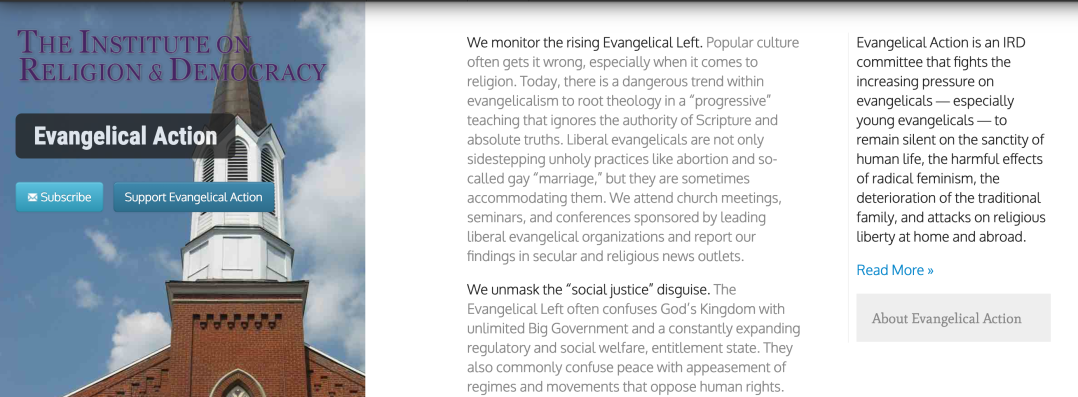

Nolte’s other affiliations likewise raise doubts about the robustness of his commitment to pluralism, at least with respect to the equal accommodation in the public square and the equal rights of those who do not share his specifically Christian commitments grounded in metaphysical propositions not accepted by the rest of us. Nolte, whose Twitter timeline is littered with retweets of Ross Douthat, Jonah Goldberg, and other right-wingers, does not have an extensive profile as a public intellectual. He has, however, contributed to Providence: A Journal of Christianity and American Foreign Policy, a product of The Institute on Religion & Democracy and The Philos Project. The Institute on Religion & Democracy’s Evangelical Action initiative claims “to fight the increasing pressure on evangelicals–especially young evangelicals–to remain silent on the sanctity of human life, the harmful effects of radical feminism, the deterioration of the traditional family, and attacks on religious liberty at home and abroad.” So many citations needed, my dudes…

Anyway, The Institute on Religion & Democracy’s publications grotesquely accuse millennial Christians of being too tolerant and clutch pearls over LGBTQ-affirming Methodists supposedly undermining biblical authority. As for The Philos Project, its about page states, “The crisis of the West is a crisis of the spirit. We have become estranged from our roots and alienated from the transcendent vision that made us great.” It is hard to believe that the language of “making us great” is accidental, and this language of supposed “alienation from our roots” has been associated with reactionary and fundamentalist rejection of modernity for a long time. It is associated with anti-Semitic stereotypes about “cosmopolitans,” against whom Nolte himself raves in his contribution to Providence. Draw your own conclusions, but to my mind, none of this does anything to assuage my doubts about Nolte’s espoused commitment to pluralism, particularly in light of how the conservative Christian framing of “religious freedom“–clearly a concern of Nolte’s, who was previously affiliated with the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown University’s Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs–tends to focus entirely on conscience and free exercise to the detriment of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. Indeed, conservative “religious freedom” arguments are being used, successfully, as a bludgeon to carve out space for discrimination and dominance in a public square in which, in conditions of pluralism properly understood, all would be accommodated equally.

With this in mind, let us return to Nolte’s article. Calling himself “a friendly observer of conservative evangelicalism,” which hardly seems to capture the true depths of Nolte’s right-wing Protestant commitments (and he later calls himself “a friendly observer/participant,” so, so much for consistency), Nolte tells us that he “thinks categorical support for Trump is both unwise and harmful for evangelicals in the long term.” Therefore “it’s even more important to understand the reasons for that support.” And then he presents us with his thesis:

Donald Trump appeared at a time during which many evangelicals’ rising expectations had turned, rather rapidly, into existential fear. Trump was uniquely positioned to exploit that moment and win over evangelicals. Yet while that support is very real, I also think it is shallower and more conditional than it appears.

While there is again some truth to Nolte’s statement, particularly on Donald Trump being positioned to use the 2016 moment, I think he exaggerates the extent to which evangelicals had “rising expectations” that dissipated “rather rapidly.” To be sure, evangelicals were somewhat confident and pretty comfortable during the George W. Bush era, but I don’t see the case that they believed they were winning their fight against same-sex marriage more or less until 2015, as Nolte suggests. Evangelicals and other conservatives, of course, spent the entire Obama era in an absolute tizzy. According to a 2010 poll, a solid 57% of Republicans believed President Barack Obama to be a Muslim, and 24% of them believed he might be the Antichrist. To be sure, evangelicals’ losses on the issue of marriage equality, culminating in the 2015 Obergefell decision, further fueled their “existential fear,” but I would like to see evidence to support Nolte’s claim that evangelicals “largely missed the broader trend that millennials were moving left on the issue far and fast.” I’m not at all sure this is true. It is also important to note that evangelicals’ existential fear, or paranoia, is not just much more than four years old, but that it is also a defining feature of conservative evangelicalism that colors evangelicals’ worldview even during what evangelicals see as the relative good times.

Even when they are somewhat optimistic, conservative evangelicals are pessimistic, because a) they are obsessed with the idea of being persecuted, believing that verses like Matthew 10:22–it quotes Jesus as saying “You will be hated by all because of my name”–mean all true Christians will be persecuted for their faith, and b) most of them believe that things are going to get worse before the rapture. In addition, irrational fear is something that’s associated with authoritarian personalities, and it’s a hallmark of the experiences of those of us who grew up evangelical in the last few decades of the twentieth century, traumatized with expectations of imminent apocalypse and mobilized for the culture wars. (Remember the satanic panic, anyone?)

While Nolte does briefly touch on the 1970s, and, in a confusing and much too brief way, on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he does not note how, in its latest iteration, the origins of authoritarian Christianity’s “existential fear” are located in the Cold War, with the ramped up panic that’s come home to roost in evangelical and radical traditionalist Catholic Trumpism dating more or less to the rise of Jerry Falwell, Sr.’s Moral Majority. Meanwhile, what Nolte considers two conflicting impulses within evangelicalism–“a tension between an expansionist view of transforming and redeeming politics, and a valid concern that religion and religious arguments will be pushed out of the public square altogether”–are two sides of the same ethos, and hardly contradictory.

The examples that Nolte provides of evangelical activism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries represent an arguably different Protestantism altogether. Today’s evangelicalism isn’t the heir of the Social Gospel we associate with the abolitionist and temperance movements; it is, instead, the heir of slaveholder Christianity inflected through the modernist-fundamentalist controversy (taking the fundamentalist side, of course), through the increasing influence of premillennial dispensationalism and an apocalyptic focus that was sharpened by the Cold War, and through the conflation of religion with anti-Communism that was largely shared by American society during the early Cold War, but which more liberal Americans abandoned around 1960, while evangelicals went on to double down on it. (Here my analysis is heavily influenced by the historical scholarship of Angela Lahr and Jonathan Herzog, particularly this book and this book.)

The relative “optimism” that Nolte attributes to evangelicals during George W. Bush’s presidency, if it can really be called that, is thus a different sort of optimism than that associated with the Social Gospel. It is, instead, a tenuous and provisional optimism that coexists with existential fear and a militant posture toward non-believers, liberals, Muslims, and anyone else perceived as a threat and a source of persecution. It is, if such a thing can be said to exist, an authoritarian optimism. Has Nolte somehow forgotten that the entire politics of the W. era was based on fear? Has he forgotten the impact of 9/11? The increasing popularity of fear-mongering FOX “News”?

Evangelicals hardly expected to keep “winning” forever, but they were, and are, also wiling to do whatever it takes to grasp and maintain political power. Theirs is an ends-justify-the-means Christianity, and thus their continuing to invoke divine authority while supporting and participating in Trump’s assault on democracy and American institutions is entirely characteristic of who they essentially are. All the while, of course, they accuse their ideological opponents of being the bullies who are “persecuting” them. This tendency to reverse the role of victim and abuser is, of course, part and parcel of abusive personalities and of authoritarianism. As authoritarians, evangelicals will accuse the rest of us of “rejecting pluralism” if we refuse to allow them total dominance.

In any case, while there might be some truth to Nolte’s thesis, inasmuch as evangelicals are capable of hoping for religious revival and for the United States to advance what they believe to be “God’s” agenda, at least for a time, Nolte leaves out the critical salient points I have raised above. It is through these sins of omission that Nolte leaves us with the impression that evangelicals’ embrace of Trump is a short-term anomaly, rather than the logical result of long-term processes and enduring characteristics of white evangelicalism. He thus plays along with the broader conservative movement’s game of pretend that would make Trump essentially the movement’s only problem, rather than a result of what the conservative movement and the GOP have become. Nolte also takes at face value what he calls evangelicals’ “valid concern” about religion being entirely excluded from the public square, something that is really quite fantastical in the American context. However, if we are going to live in a truly pluralist country, then strictly religious arguments should not be made binding through coercive law on those who do not share the religious beliefs behind the arguments and cannot be persuaded by mutually accessible arguments. Nolte fails to deal with this tension.

There are a few other criticisms I would like to raise of Nolte’s piece. For example, in his discussion of “evangelical nice” and his reference to the character Ned Flanders from The Simpsons, Nolte attempts to paint evangelicals as essentially benign, incapable of acting aggressively to defend their own interests and so turning to a strong-man like Trump only as a result of ostensibly very recent “existential fear.” Those of us who have lived and left evangelicalism can tell you that “evangelical nice” and rabid belligerence often coexist in the same evangelical.

In many cases, all you have to do is make the wrong comment, however innocently, to witness the transformation of a “nice” evangelical into an angry culture warrior, like whenever the subject of Black Lives Matter comes up with one of my uncles, or like the time when one of my aunts, who is generally kindly and hospitable, turned on a dime during one lunch into a fearsome and forceful defender of George W. Bush’s use of torture as a result of some comment I’d made. Believe me, “nice” evangelicals can be “bellicose, bombastic, and insulting” under the right circumstances. Probably even Flanders could. As for Nolte’s data-free nod to imagined evangelical “millennial moms” who do not like Trump, this is simply a red herring. I know plenty of evangelicals who will say that they don’t like Trump. This will not stop them from voting for him in 2020, or for voting for similarly authoritarian candidates whose lifestyles and rhetoric are more in keeping with their own.

Nolte makes much of churchgoing evangelicals’ initial lack of robust support for Trump during the primaries ahead of the 2016 presidential election. This ignores the fact that Ted Cruz’s political ideals are really no less authoritarian than Trump’s, however, even if Cruz is slicker and smoother about it. It also ignores the critical fact that after the primaries regular church attendance became a predictor of higher Trump support among white evangelicals. Whether through an inexcusable lack of engagement with the relevant data or intellectual dishonesty, it is only by leaving out churchgoers’ higher Trump support that Nolte is able to assert that church attenders are less susceptible to existential fear because church provides them with “social connection.”

Again, I would raise the ongoing evangelical abuse crisis to suggest that evangelical church communities are far from healthy sources of social support, but I should note that Peter Beinart made much the same fallacious move in his April 2017 Atlantic article “Breaking the Faith.” Meanwhile, Nolte’s attempt to decouple ethnic from religious populism in the U.S. context is also unconvincing. Both Nolte and Beinart are clearly invested in the notion that religion is in its essence a moderating force and a social good, but this notion has no basis in fact whatsoever. I would suggest that both of them read sociologist Phil Zuckerman’s Society Without God: What the Least Religious Nations Can Tell Us about Contentment, a study of lived secularism in Scandinavia, for a thorough debunking of the claim that a less religious society will be a more illiberal one. Both men are completely blinded to the very real threat of religious authoritarianism, which is in fact the most urgent threat to democracy and human rights we face in America today. And if Nolte is wrong about the temporary nature of evangelicals’ “existential fear” driving their politics–and he is–then he is also wrong to predict that, as evangelicals get more of what they want, they will become less authoritarian.

It’s time for us to wake up and start acting accordingly. One step we can take is to change the way we discuss evangelicalism in the public sphere. The Bulwark and other outlets should stop letting evangelicals play without an opponent. Exvangelical and other critical voices do not just deserve to be heard. Our perspectives will prove essential to the future of American democracy itself–if, that is, American democracy has a future.

You know, the Capitol Ministries people came to my country for meetings with senators. Our main paper covered that.

In Costa Rica people don’t like the evangelical influence, so, the main newspaper of the country covered the event and made an editorial in unfavorable terms.

https://www.nacion.com/el-pais/politica/consejeros-biblicos-de-vicepresidente-de-ee-uu/QQWTUDQFSFEXVF5IJOLQKLLURQ/story/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad to hear there’s resistance to their presence in Costa Rica.

LikeLike

I appreciate the conservative opponents of Trump, but they still don’t get that Trump’s behavior was a feature, not a bug, to evangelicals. They still don’t comprehend that evangelicalism has been poison for a long time. Politics isn’t ruining religion, religion is ruining politics.

Before the 2016 election, I wrote that Trump’s popularity with evangelicals (which I doubt he even understood at the time) was precisely because his behavior mirrored theirs in so many ways:

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2017/7/3/1677547/-Evangelicals-Attraction-to-Trump-is-Deep-and-No-Mystery

I followed that up about a year ago:

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2018/5/19/1765547/-What-Shapes-Evangelical-Views-and-Why-Their-Continued-Support-of-Trump-is-Logical

And just for fun, here’s a recent piece about Falwell Jr.

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2019/1/2/1822916/-Falwell-Jr-denies-Jesus-Christianity-to-the-Washington-Post

LikeLiked by 1 person

Crisstroop I just ran across your blog this morning. “Exvangelical” I like it and I can relate. Though “Recovering Evangelical” may always be closer to the truth. Looking forward to doing more reading and getting to know you better.

Meanwhile “God is Love.”

LikeLike