If there’s one temptation America’s major newspapers and magazines seem unable to resist, it’s the temptation to normalize America’s white Christian extremists–including traditionalist Catholics, yes, but especially Evangelicals. On the whole, this 81% Trump-voting population represents a clear and present danger to American democracy and the future of human rights, but time and again The Washington Post, The New York Times, and above all The Atlantic fall over themselves to allow the most well spoken and seemingly reasonable conservative white Evangelicals to misrepresent their history and their movement as respectable, as capable of accepting pluralism and operating in democracy in good faith, indeed, as almost moderate. The most recent noteworthy instance involves Michael J. Gerson’s “The Last Temptation,” published in The Atlantic on March 11, 2018. I’ll return to his essay in a minute, but first I want to note what’s wrong with the broad pattern it represents.

Too frequently “respectable” voices of white Evangelicalism such as Gerson and Russell Moore (president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission and a key signer of the hateful anti-LGBTQ Nashville Statement) are granted the space to frame elite discussions of their movement essentially uncontested. Failure to include critical perspectives, such as those of ex-Evangelicals (often now referred as the Exvangelical community), is poor journalism. But it is also more signficant than that. In making this devil’s bargain with the smooth and slick #FakeModerates of the Christian Right, in essence providing them with free face-saving PR for a movement that does immense harm and that in the aggregate can fairly be described as Christofascist, America’s major media outlets have enabled the Right’s shift of the Overton Window.

It is that shift that has made it possible for the repulsive and amoral Donald J. Trump–a man who has no respect for the rule of law and who gleefully erodes our democratic norms at every turn–to occupy the presidency. This normalization of that which should not be acceptable in any decent society, of those forces that, unfettered, will dismantle any and all human rights protections for those outside the in-group and impose authoritarian rule, needs to stop, if we are to have any chance of salvaging American democracy from the Trumpist authoritarian onslaught. By setting the bar ever lower in terms of what is acceptable and even praiseworthy, we only embolden white supremacists and radical Christians in their worst impulses.

Yet instead of drawing lines in the sand to demarcate what is not acceptable in a pluralist, secular democracy, too many of America’s leading commentators and gatekeepers have continued to lower the bar and to normalize the extreme and the anti-democratic. Witness, for example, the rehabilitation of George W. Bush and his administration, not least in the celebration of Gerson himself, who was Bush’s chief speechwriter from 2001-2006. As Trump moves to elevate Gina Haspel, one of the architects of Bush-era torture policy, to head the CIA, should Gerson’s membership in Bush’s White House Iraq Group not give us pause? I distinctly remember arguing with an Evangelical aunt over the morality of “legalizing” torture after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke. She vigorously defended the president’s approach, and it now appears that white Evangelicals’ new champion, Trump, is charting a course to “make torture great again.”

So what, then, of Gerson’s essay itself? Let’s look at it from a few angles. Although I don’t understand why so many commentators seem to view this as an impressive achievement, given how much excellent historical research on Evangelicals has been published in recent years, Gerson does summarize much of the basic history of Evangelicalism correctly. Nevertheless, his history is skewed both in its framing and in its strategic omissions.

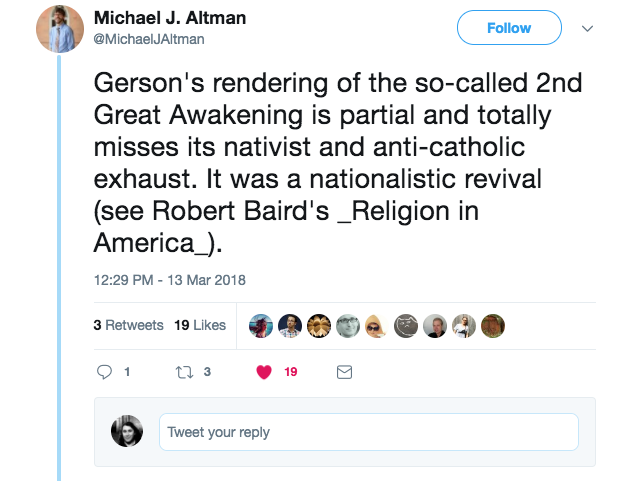

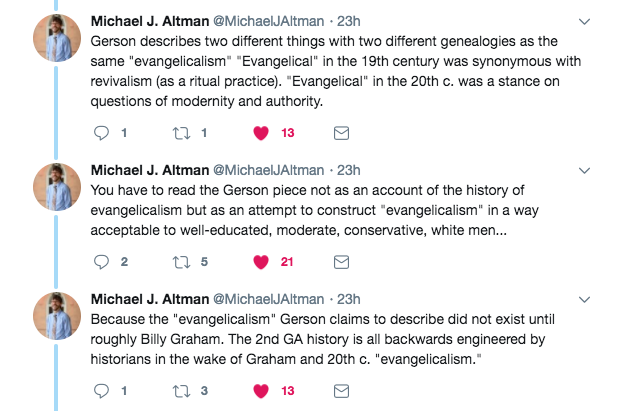

One could certainly argue, as Michael J. Altman did on Twitter, that there is a fundamental discontinuity between the twentieth-century Evangelicalism that has its roots in the history of fundamentalism vs. modernism, on the one hand, and the revivalist Evangelicalism of the nineteenth century, on the other. Although, of course, the Second Great Awakening, like twentieth-century white Evangelicalism, was also characterized by animus toward “the Other” and a type of Protestant nativism:

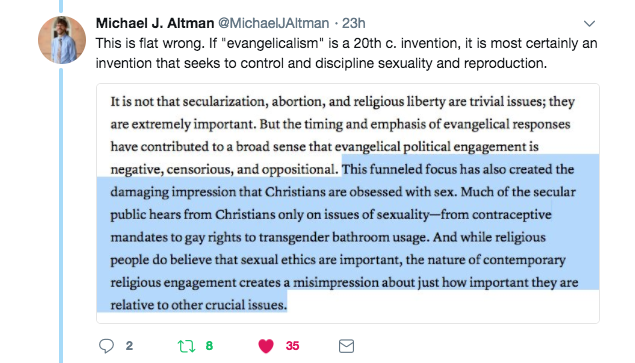

Altman also points out that Gerson’s denial that “Christians are obsessed with sex” is nonsense (note too how Gerson uses the term “Christian” to mean conservative Evangelicals like himself, effectively claiming a monopoly on the term, which is precisely the way we I learned to use the term growing up Evangelical). Growing up in Gerson’s Evangelicalism, I, along with my entire seventh-grade class at Colorado Springs Christian middle school, was essentially badgered, fear-mongered, and coerced into signing a purity pledge at a class “retreat.” We were told to pray to ourselves and to sign the pledge only if we were sincerely making a commitment, but we were not sure whether we might be expelled if we didn’t sign, and this is an incredibly harmful burden to place on adolescents in the first place. Of course we signed–literally under duress. Thanks to recent and ongoing discussions of Evangelicalism’s toxic purity culture, I know that my experience was not atypical.

I suppose there is a slight chance that a man as intelligent as Gerson could, as a Wheaton educated privileged white man, be blind enough to be sincere in his denial that Evangelicalism is fundamentally obsessed with sex. Intent to mislead, however, is not necessary for speech like Gerson’s to be considered gaslighting, and Gerson’s statement here sure seems like gaslighting to me. It is indisputably a misrepresentation of conservative Evangelicalism, one that makes the faith seem benign when, in this respect, it is utterly destructive. If you don’t believe me, just read any number of blog posts or Twitter threads by ex-Evangelicals about how much harm purity culture did to us–check out, for example, No Longer Quivering, Homeschoolers Anonymous, No Shame Movement (see also its Twitter account), Fundamentally Free (an intersectional ex-fundamentalist group blog managed by Mandy Nicole), and spoken word poet Emily Joy’s Twitter, for starters:

Meanwhile, Evangelicalism is facing an unfolding abuse scandal that will most likely prove to be larger than that of the Catholic Church when the dust settles. This is no coincidence, but is a direct result of the Evangelical obsession with sexuality that Gerson wants to pretend is inconsequential or non-existent. Has Gerson read any of the #ChurchToo tweets, I wonder?

Gerson also represents himself as an exemplar of “compassionate conservatism,” touting his role in the Bush era program known as PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief). PEPFAR has undoubtedly achieved results by providing treatment to those suffering from AIDS, but the program could have done much more with respect to prevention if not hampered by the conservative Christian obsession with sex Gerson wants us to pretend doesn’t exist. In addition, a more honest accounting of Evangelicalism’s history with AIDS would have to note that the United States’ initial failure to respond seriously under Reagan was primarily the doing of white Evangelical Christians, many of whom still consider AIDS to be divine punishment for homosexuality.

So, what about race? As with Evangelicalism’s authoritarian policing of sexuality and gender roles (which is a feature, not a bug), on matters of race, Gerson also deflects, mostly through omission, in a way that in my view qualifies as gaslighting. Our elite media outlets resist saying so out loud, but there is simply no honest way to write about the history and contemporary realities of white Evangelicalism without locating the subject as inextricably connected with slavery and white supremacism. In an excellent essay first published on Forbes around the same time Gerson’s article was published, Chris Ladd was bold enough to tell the truth about “Why White Evangelicalism is So Cruel.” Gerson would prefer to focus on the fact that his alma mater, Wheaton, was founded by abolitionists, leaving out the crucial facts that a) the direct origins of today’s Christian Right lie in resistance to integration and opposition to civil rights legislation, and b) Wheaton has never even come close to exhibiting anything like robust racial equality:

Gerson’s omissions on race seem particularly tone-deaf and out of touch given the still poor record of Christian schools and colleges on race. See, for example, the current scandal swirling around Faith Christian Academy in Arvada, Colorado, which recently fired teacher Gregg Tucker after he used a chapel service to address the school’s Trumpist ramped up climate of racism. In light of the above, Gerson’s comments seem entirely inadequate:

I do not believe that most evangelicals are racist. But every strong Trump supporter has decided that racism is not a moral disqualification in the president of the United States. And that is something more than a political compromise. It is a revelation of moral priorities.

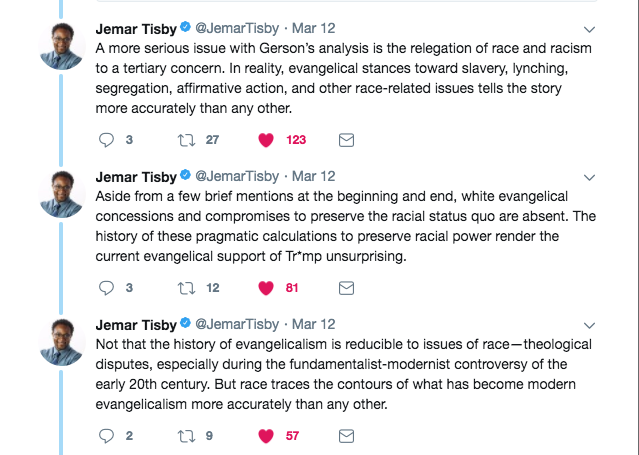

In his comments on race, Gerson resembles, at best, the white moderate with whom Martin Luther King, Jr. found himself “gravely disappointed.” African-American journalist, commentator, and Christian thought leader Jemar Tisby did not mince words about this in his Twitter thread on Gerson’s article.

And yet from the reactions to Gerson’s article of progressive white Evangelicals who should know better, you could be forgiven for thinking Gerson was a messenger of God himself, sent down from heaven in a chariot of fire to deliver justice. This hyperbole–religion journalist Cathleen Falsani even had the gall to use the hashtag #Resist in one of her tweets about Gerson’s article–is beyond unhelpful. And it is exactly what I mean by lowering the bar.

Sojourners founder and editor Jim Wallis was also bizarrely, unduly effusive:

Why should Gerson be awarded any brownie points, let alone be praised to the moon and back, simply for taking issue with his fellow white Evangelicals’ support for Trump and mildly suggesting that Muslims ought to have religious freedom too, when his criticism, such as it is, does not get to the heart of the issues? Nor does he deal adequately with his own complicity, as a man who worked directly with Karl Rove, in the politics of “truthiness” and the unleashing of naked Christian Right authoritarianism. Gerson’s criticism represents at best minimal human decency, and is essentially non-threatening to the Christian Right’s power. Even worse, his article’s emotional rhetoric is designed to elicit sympathy for Evangelicals–Gerson wants us to bemoan Evangelicals’ “status lost” after the Scopes trial instead of recognizing that anyone clinging insistently to “alternative facts” should lose status in a functional democracy. “Alternative facts” go hand in hand with the Christian Right, and indeed with authoritarian governance.

So no, Gerson does not deserve the status of hero just for lobbing some choice words at his coreligionists that are directed entirely at a surface issue–their Trump support–without getting to the roots of that Trump support. The rot in Evangelicalism is pervasive, but the likely ultimate impact of Gerson’s commentary will be to elide the deeply-rooted authoritarianism inherent in white Evangelicalism. And our leading journalists and commentators are letting him get away with it.

In contrast to the liberal white Christians mentioned above, my initial reaction to Gerson’s article was viscerally negative. Thinking through my reasons for that in a more systematic manner in this blog post, I feel more justified in my reaction than ever. And here again I’ll put out the call for readers to tweet the hashtag #EmptyThePews at The Atlantic, at Gerson (who is also a regular columnist for The Washington Post), and at other offending outlets and journalists, demanding that they do better in their coverage of white Evangelicals by including more nuance and more critical perspectives.

I wasn’t the only one to react negatively to Gerson’s piece. Indeed, one of America’s shrillest culture warriors–a man who embodies the sexual obsession of conservative Christianity that Gerson is in denial about–strongly criticized Gerson for not being sympathetic enough to Trump-supporting white Evangelicals. I am speaking of National Review’s David French, whose current Twitter avatar is a portrait of the hateful historical authoritarian John Calvin, and who used his platform, in typical bully fashion, to represent the bullies as the bullied. In his screed, French insisted that Gerson had not taken Evangelicals’ ostensibly legitimate concerns about “religious liberty” seriously. Of course, Evangelicals have coopted the language of “religious freedom,” just as they use the term “Christian” in a monopolizing way, and what they mean by this Orwellian usage is the “liberty” to impose inequality in the public square and to enforce laws on all of us derived from beliefs that the rest of us do not share. In other words, they want not liberty for all, but the exclusive right to rule over the rest of us in an authoritarian fashion. French keeps using that term, but I do not think it means what he thinks it means.

Meanwhile, Gerson’s reaction to French’s diatribe is very telling. Gerson called French’s piece “thoughtful.”

In other words, Gerson is essentially on French’s side; he’s just more polite about it. That side is authoritarian and anti-democratic, and we need to start treating it as such. While white Evangelicalism is not salvageable as a faith community that deserves to have social influence or play any role in shaping public policy, there is one thing I agree with Gerson about. Toward the beginning of his article, he noted that, despite the term’s increasingly poisonous connotations, he is “hesitant to abandon the word evangelical.” I, for one, think he should keep it.

I think white Evangelicals should have to own all of the white supremacist patriarchal horrors they have unleashed throughout American history, and all of the horrors they are unleashing in the present under their Trump regime. No amount of rebranding should be adequate to “save” their movement. If we are to survive as a democracy, we need to reduce their influence as much as possible, as quickly as possible, because, make no mistake, this is not a religious group that ultimately respects the rule of law. These are fundamentalists, driven at base by a need for power and control. They want to dominate. The media should not help them achieve that goal by normalizing them.

But if they actually call out Christian evangelicals for what they are, said evangelicals might get angry and boycott, etc., which would hurt their bottom line. The simple truth is that for-profit media will never be able to give an “honest” narrative because their entire goal and purpose is to make a profit. Unsurprisingly, they don’t do things they feel will impede their ability to make a profit. It’s not an accident that we have a President who “may not be good for America, but [is] damn good for CBS”, according to CBS President Les Moonves. Over here from the socialist perspective, it’s telling that you just about never hear anyone with a prominent platform talk about the complicity of the corporate media in enabling right-wing authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. If you want to know what those in power *really* don’t want you to talk about, look at what’s not being said in the “mainstream”. True censorship is not punishing people for espousing “bad” thoughts; it’s making the very thought unthinkable, such that it never even occurs to people in the first place.

LikeLike

While this article raises a fascinating number of things, unfortunately, it’s pointing to a big pile of things together and assuming it’s one enormous thing. I grew up in the heart of an evangelical region and the “movement” is a patchwork of dozens of competing faiths, ideologies, cultural groups, and occasional demagogues only barely held together politically by people who want to profit by directing American faith.

Obviously, certain individuals want to portray the movement as more united than it is but the very fact Black evangelicals exist alongside the most racist of their kind shows it is really a stew that cannot be said to have anything other than a loose collective identity. I say that as an extraordinarily Leftist Christian who can often find common ground on some issues only to find complete stonewalling on others–only for the issues to change with the next evangelical I meet.

LikeLike

I grew up in it too, and have studied Evangelicalism and the intersections of Christianity, society, and politics, and I strongly disagree with your take. Sociologically, conservative, essentially white Evangelicalism absolutely holds together as a group through many historical, parachurch, intrachurch, and other institutional, cultural, and personal ties, from the National Association of Evangelicals, to Christian colleges, to inter-denominational missionary organizations and efforts, to campus ministries like InterVarsity and Cru, to Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council.

To insist on Evangelicalism’s ostensible “diversity” is a deflection that serves to distract from how harmful and abusive white Evangelicalism has overwhelmingly become. I often see this deflection from progressive Christians, and it strikes me as an expression of defensiveness, consciously or not. #NotAll defenses aren’t helpful when we’re talking about structural issues. Yes, some 15-20% of white Evangelicals are moderate to progressive. They’re outliers, however. And to lump African-American Evangelicals and other Evangelicals of color together with white Evangelicals as a single social group makes zero sense; Sunday morning remains the most segregated time of the week in America. There are of course a number of Evangelicals of color who have integrated into what is essentially white Evangelicalism – but many are leaving (see this piece by Cambell Robertson: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/09/us/blacks-evangelical-churches.html) in light of white Evangelicals’ embrace of Trump, with 81% voting for him and 78% still approving of his performance. Those are definitional figures. There are differences within these multi-denominational thing, certainly. But sociologically, it is still very much a thing.

LikeLike

I have followed you on twitter since I joined up after the election. I am an older lapsed Catholic who has always thought of religion as the opiate of the masses. Your scholarship on evangelism is intriguing. It’s made me think of our collective American religious history in a whole different way. It’s been mangled from its origins and morphed into almost the opposite notion of what it started as. I’d like your thoughts on The religiosity of black Christianity. This sounds very simplistic, but why do black Christians with strong convictions make me wish I had their faith, while white Christians with strong convictions make me cringe and revel in my antireligiosity? Because I’ve had so much illness in my middle class white family I have never met any finer people than the Christian caretakers of many African origins from West Indian to Nigerian to American? They mostly seem to be unspoiled by the evils that have crept into white evangelism. They wear their religion in their sleeves but it never offends me. Is it because of their universal struggle for freedom and equality?

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the American context, I think this has everything to do with slaveholder religion vs. liberationist Christianity reclaimed and transformed by slaves and their descendants in conditions of white supremacism. I too have deep admiration for the Black Church.

LikeLike

Full of caricaturing, false generalization, and the usual insistence on subsuming Christianity into a leftist cultural model with no edges that offend anybody. If your point was specifically how support for Trump presents certain problems for evangelicals, that’s a different thing, although it does have an answer. If you or other people here were interested in the answer, if it would make any difference at all, I’d take the time to lay it out. But like so many proudly “ex”-evangelicals, lapsed Catholics, etc., the real point is always to get to a broad, grandiose condemnation of any version of Christianity or Christians outside that left-friendly version, along with proving superior enlightenment, evolution, and virtue, and getting high-fived by people who already think as you do.

I do _not_ think being Christian necessarily means being right of center or Republican, and certainly it doesn’t require blind allegiance to Trump or disregard of his personal flaws. But you’re missing the point.

LikeLike

Whew! What can I say? This isn’t scholarship, this is a diatribe by someone who hates a group of people who are so diverse he can’t even grasp it. Generally speaking, when people reveal so much hate for another group, there are some underlying reasons. Perhaps the moral standards offended or were too high for this person to attain. Perhaps it’s revenge based on some personal experience. What is not taken into consideration is that many conservative Christians, Catholic and Protestant, couldn’t vote the Clintons back into the White House for many good reasons. I, as a Reformed Faith Christian, couldn’t vote for Trump due to his character issues, but I also couldn’t vote for Clinton due to her and her husband’s character issues either. No writer, even a Michaei Gerson, is able to treat totally the issues involved. We have what we have. We’ve had some other very morally-bankrupt presidents before Trump. Would this writer go after the Democratic Party for its racist role in our history? Probably not. He prefers to attack Christians who have been commanded to “turn the other cheek.” And I disagree with Michael Gerson also on some issues, but he didn’t deserve this. That election didn’t give any good choice. Can we be honest?

LikeLike

Apparently at least you cannot be honest. The projection is strong with you. Have a great day!

LikeLike